U.S. Department of Energy Doubles Down on Shale Optimism

February 12, 2018

The U.S. stock market is not the only thing that’s gotten overheated in the last few years. Exuberance over U.S. energy output has hit a record high as natural gas production has reached its all-time peak, and oil production nears highs not seen in 47 years. Thanks to the so-called “shale revolution” (tapping previously inaccessible fossil fuels in shale rock deposits through the use of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling technologies), the U.S. government has green-lighted liquefied natural gas export terminals and pipelines and lifted the ban on oil exports. The statistical arm of the U.S. Department of Energy—the Energy Information Administration (EIA)—predicts that the United States will become a net energy exporter in the next five years, a status we haven’t enjoyed since Eisenhower was president.

Although shale development represents a remarkable technological achievement (made possible by cheap loans and questionable finances), the EIA seems to be betting heavily on the long-term prospects of tight (shale) oil and shale gas production, apparently in the erroneous belief that what goes up must keep doing so. This despite ample warning signs that the “shale revolution” will be a short-lived phenomenon. In fact, the higher production goes, the faster and sooner it will decline.

Since 2011 my colleague at Post Carbon Institute, David Hughes (an expert on fossil fuel production who worked for the Geological Survey of Canada for 32 years), has been sounding the warning bell about the danger of betting our energy future on shale. Through intensive analysis of oil and gas production data, he has identified a clear pattern of quite rapid boom and bust cycles in shale plays.

In 2013 Hughes showed that the EIA’s estimates of technically recoverable tight oil in California’s Monterey Formation (at the time estimated to be nearly 2/3rds of the entire resource in the lower 48 states) were grossly unrealistic. A few months later, the EIA downgraded their estimates by 96%. And yet, despite their own admitted track-record of significantly over-estimating production, the EIA doesn’t seem to learn.

Last week, Post Carbon Institute published Hughes’ analysis of the Energy Information Administration’s Annual Energy Outlook 2017, which found that the EIA’s forecast for shale gas and tight oil production through 2050 was “extremely optimistic.” Our hope was that timing publication of this analysis would encourage journalists and policymakers to receive the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2018 with some caution, and perhaps even to ask critical questions.

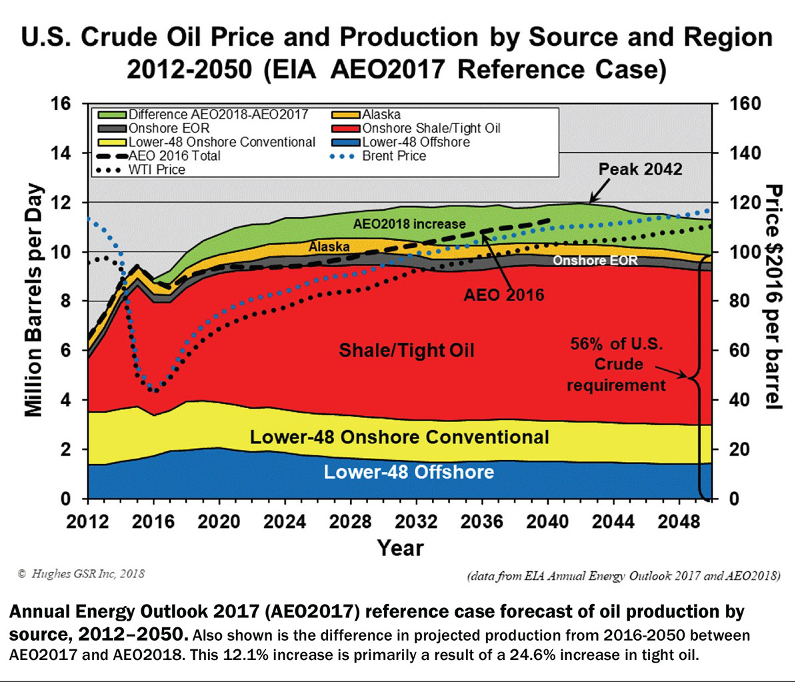

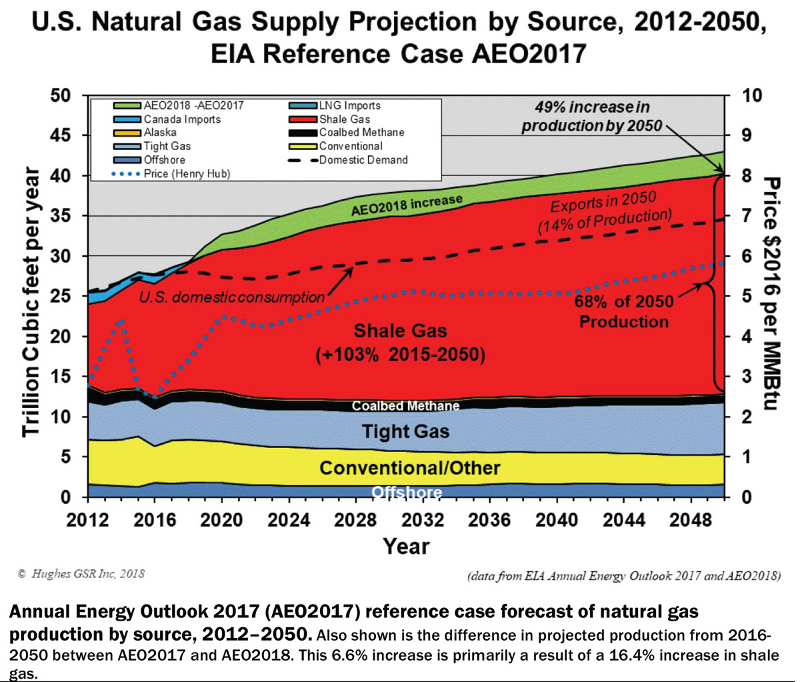

At this point, that’s our only hope since the EIA itself seems incapable of stepping back from the blackjack table. We thought that the AEO2017 made an easy target for doubt, but the EIA upped the ante with the AEO2018, which they also released last week. They’ve raised their estimate of cumulative tight oil production through 2050 by 25% and shale gas by 16% over last year’s already remarkably optimistic forecast.

I don’t reprimand the Energy Information Administration lightly, or with any pleasure. I’ve met staff at the EIA and believe that as a whole they are well-intended and provide the American people with a fantastic service in collecting and providing energy data. It’s just that they are lousy at forecasting. And this matters. It matters a lot.

Wouldn’t it be refreshing if U.S. energy policy and investments were based on more than what’s thought to be technically or economically possible? Perhaps on what’s ultimately best for our citizens? Considering the dire need to mitigate climate change and other environmental and human health impacts, what’s best for our citizens is to ramp down fossil fuel production as quickly as possible. But those concerns are clearly not prioritized—certainly not by the Trump Administration, but not under the Obama Administration either.

The crazy thing is that even on its own merits, the belief in long-term oil and gas abundance is a mirage. These are finite resources and shale oil and gas deposits deplete at a faster rate than conventional resources. (Depletion rates for wells average 70-90% in the first three years, while annual decline rates for entire fields are 20-40%—meaning that every year up to 40% of production has to be replaced just to stay at the same level.) Wishing it to be otherwise may be politically expedient, but it’s not the basis of sound energy policy. Yet that is precisely what the EIA is offering.

Unfortunately, the reference case forecasts made by the EIA every year, which are taken with nary a question by policymakers on Capitol Hill and at the White House, nor the mainstream media, have an enormous impact on the direction of U.S. energy policy. Right now, we’re raising the stakes on a weak hand.

Feature photo credit: Naja Rider/Shutterstock.com