Six Foundations – Presentation to Community Action Partnership

January 16, 2016

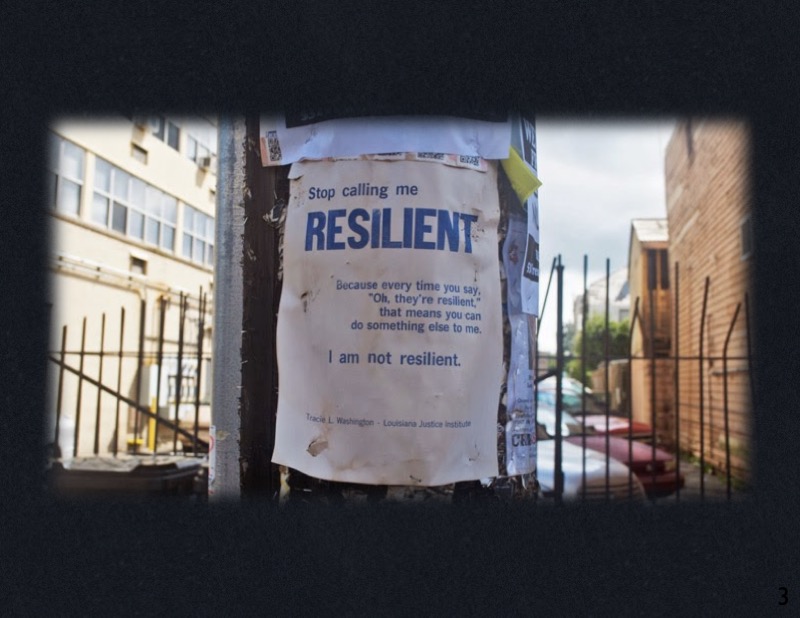

American towns and cities face a series of economic, environmental, and social justice challenges that hit the most disadvantaged communities especially hard. Therefore, it’s no surprise that the idea of “community resilience” has gained popularity in recent years. But too often resilience is viewed as “bouncing back to normal” after disruptions like Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy.

In the below presentation to Community Action Partnership, Post Carbon Institute’s Executive Director, Asher Miller, discusses why this definition of resilience is incomplete and explore why and how community based organizations can build community resilience that is more sustainable, transformative, and just.

Thank you for that introduction Denise. Before I begin I just want to thank the board and staff of CAP for making it possible for me to join all of you this morning. And I also want to thank each of you for the hard work and dedication you put in, day in and day out, to improve the lives of so many people across this country. I mean that, sincerely.

I wanted to speak with you today about why building community resilience is such an important strategy and share with you some things to consider as you wrestle with the question of how to build resilience in the communities where you live and work. These are taken from a report we recently published called “Six Foundations for Building Community Resilience” which you can find here.

As most of you know, a few months ago marked the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. In a speech marking the anniversary, President Obama talked about the extraordinary resilience of this city and its people and how they serve as a model of resilience for the rest of the country.

Some of you were lucky enough to join the tour of the 9th Ward yesterday afternoon to see firsthand some of the impacts of Katrina and the progress and challenges that the people of New Orleans have made to build resilience in its wake.

Resilience. Since Hurricane Katrina—but particularly after the Great Recession hit and then Hurricane Sandy ravaged New York and New Jersey—that word has grown more and more popular.

But what do we mean by resilience? And what are we building resilience for?

Typically, people think of resilience as the ability to bounce back from disruptions and return to “normal.” Communities have always prepared for emergencies – that’s why we have police departments, fire departments, insurance companies.

But we now live in a hyper-connected world, where something that takes place on the other side of the planet – let’s say the crash of the Chinese stock market – can have a profound impact here at home.

And so when we think about building community resilience, we have to recognize that disruptions can come in many forms and from many sources. They may take an acute form, like a Hurricane, or be chronic – like the economic hardship that can hit a region when its primary industry vanishes.

Resilience has become a buzzword in recent years as the risks posed by climate change have become more and more clear.

But while climate change is likely the most existential threat we face, it’s far from our only challenge.

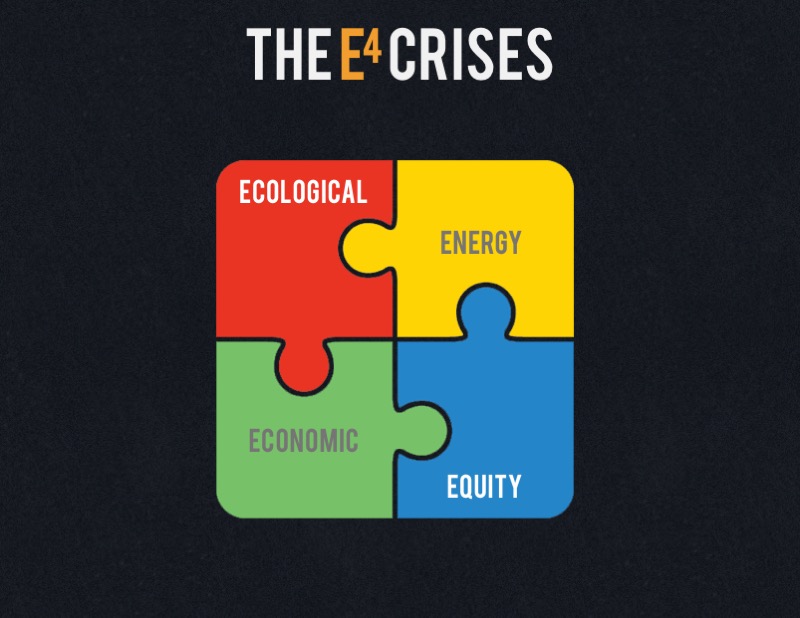

At Post Carbon Institute, we tend to organize these challenges as a set of four distinct but intertwined challenges that we call the E4 crises. These influence and multiply each other in complex and unpredictable ways.

We view them as “crises” because – even if we can’t predict exactly how they will manifest themselves globally or locally –they are pushing us towards profound changes.

I want to spend just a few minutes summarizing these, though they each warrant much more discussion than we can afford right now.

Let’s start with the environment because, after all, if we don’t have a functioning planet we won’t have a functioning society.

I already mentioned that climate change is likely the biggest ecological threat we face, but we’re dealing with a whole host of environmental issues – toxins, the depletion of fresh water and top soil, the collapse of fish stocks, deforestation, and so on.

Simply put, we are overshooting the capacity of the planet to support our numbers and our rate of consumption.

And when other species and previous societies have overshot their support systems, it hasn’t ended well.

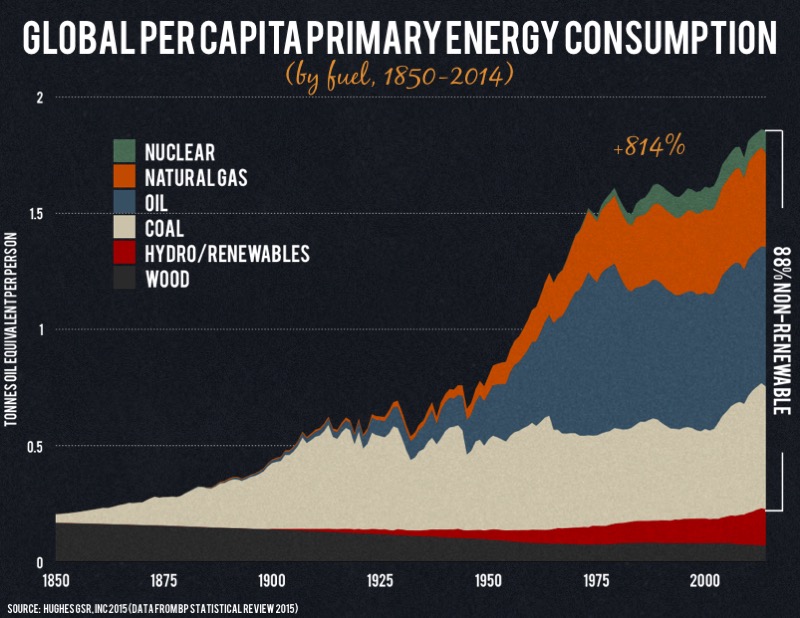

So what’s caused this overshoot? Ultimately, it comes down to our use of energy. Specifically, our ability to harness fossil fuels – coal, oil, and natural gas.

For 99% of our history as a species, we lived off diffuse and variable sources of renewable energy – sun, wind, water, and muscle power. By their very nature, these sources of energy forced us to live within a kind of budget… though that budget wasn’t always allocated equitably or peacefully.

But when we discovered fossil fuels, it was like winning the lottery. And like a lot of lottery winners, we started spending like crazy.

Fossil fuels provided us with an incredibly dense, transportable, and consistently available source of energy that packed an enormous punch.

This is particularly true of oil. It’s hard to believe but one barrel of crude oil – which currently costs somewhere around $35 – packs the energy equivalent of 25,000 hours of hard human labor. So it’s no wonder why we mechanized everything we could.

After all, why farm this way…

When you could farm THIS way?

Since the beginning of the industrial revolution, per capita energy consumption around the world has grown eight fold as we consumed more and more fossil fuels.

Keep in mind that human population has also grown exponentially in that time, thanks to the industrialization of agriculture and the spread of modern medicine.

The fossil fuel revolution led to a great many advances, including a tremendous economic boom that, for a while at least in the U.S., raised the standard of living of most Americans – though certainly some more than others.

But particularly in recent decades, the benefits of that boom has created diminishing returns for a larger and larger number of people.

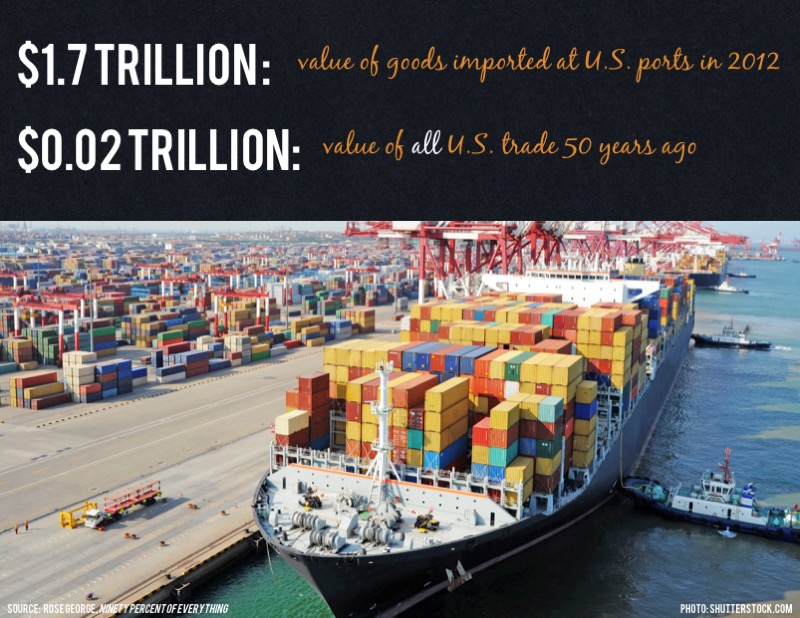

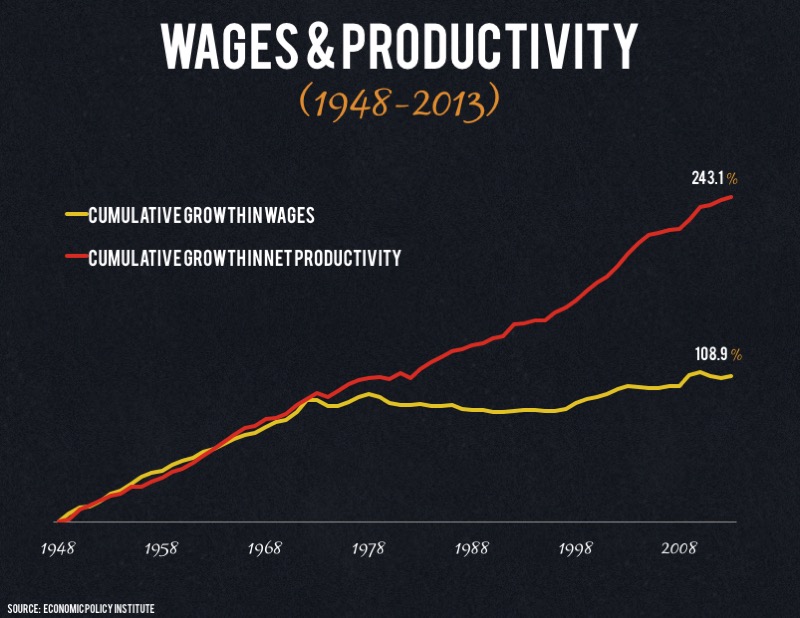

Cheap fossil fuels allowed businesses to replace human labor with machines that could be much more productive, or with cheaper labor from overseas.

This helped consolidate wealth in the hands of corporations who were the most successful at being the most efficient, and it significantly undercut the power of Labor.

And as trade expanded, the US economy became more oriented around the financial and service sectors.

Wages stagnated and the wealth gap grew.

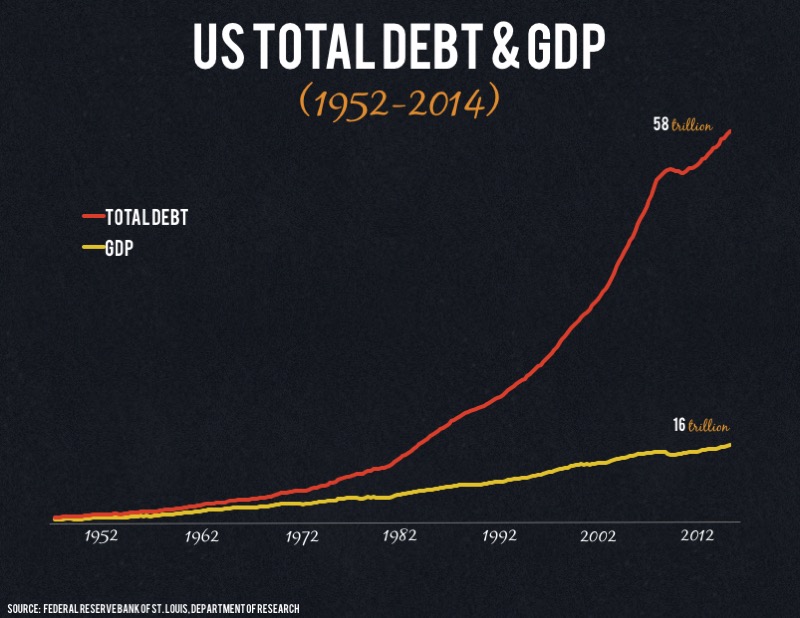

So, too, has the gap between economic growth and debt grown. In the 1950s the ratio between GDP growth and growth in total debt was about one to one. But starting in the 1970s, the rise of debt began to outpace GDP.

In the 2000s, it took about five and a half dollars of debt for every one dollar of GDP.

But how is that debt ever supposed to get repaid? Only through more economic growth.

Since the Great Recession, governments and central banks have done everything in their power to kick-start the economy and return to the days of robust growth.

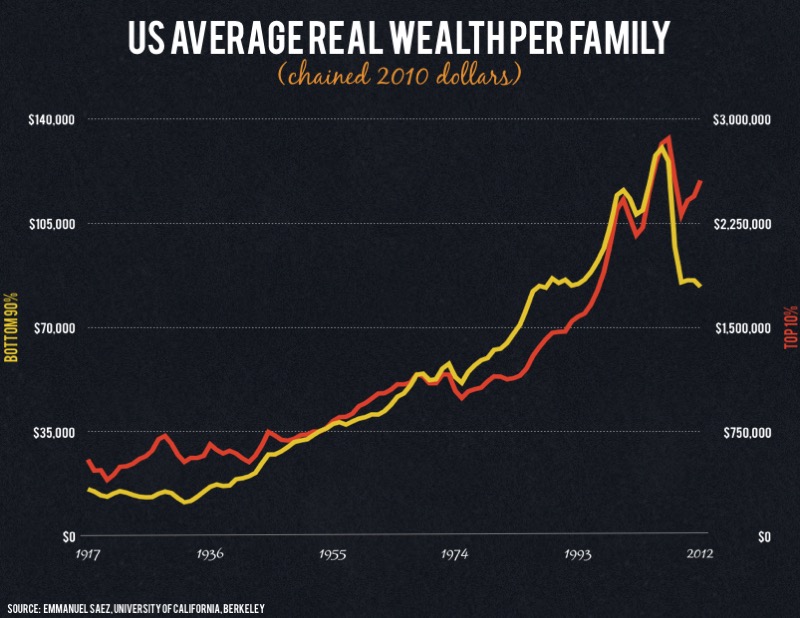

But despite all those efforts, growth has been anemic and has gone disproportionately to the wealthy. Some are calling this era of slow growth or stagnation a “new normal” and warn that inequality could worsen.

A major driver of this “new normal” is that the days of the fossil fuel boom are coming to an end.

Not only do we need to leave fossil fuels in the ground if we’re to have any hope of a livable climate, but we’ve come to discover that fossil fuels aren’t so cheap, after all.

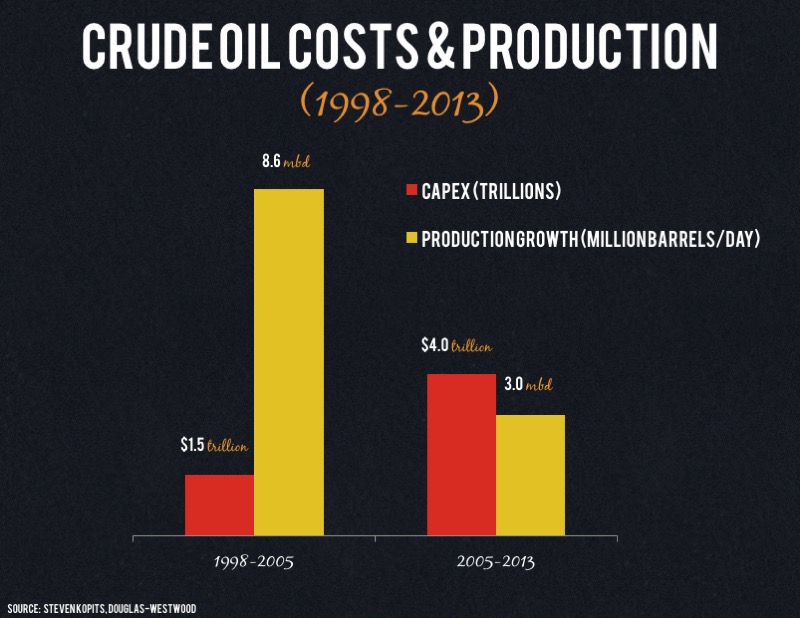

Industry now has to go to extreme lengths to extract more oil, coal, and natural gas. And these new sources, particularly of oil – deepwater oil, tar sands, fracking – cost more to produce, have much greater environmental impacts, and a far worse energy return on investment.

Right now, there’s lots of talk about the huge drop in oil prices that took place over the last few months. But ignored is the reality that over the last eight years oil companies have had to spend 11% more annually on capital expenditures to gain less than 1% growth in crude oil production.

The drop in oil prices means they can’t afford to invest as much in future production. The environmentalist in me thinks that’s great. But the energy realist in me recognizes how much our modern life is dependent on growing supplies of oil.

After even just a short exploration of these issues, you’re probably wondering why we should even bother building resilience at the community level at all when the E4 crises are ultimately national and global in scale?

I’ll talk in a minute about why work at the community level. But first, it’s important to take a closer look at the concept of resilience itself.

When we begin to think about community resilience, one of the first places to turn is the field of ecology.

In resilience science, resilience is defined as “the ability of an ecosystem or species to absorb disturbance and still retain its basic function and structure, or “identity.”

For example, a maple-beech forest ecosystem might experience a wildfire, drought, or infestation.

If it is sufficiently resilient it will recover from individual incidents and adapt to longer-term changes, all while keeping essentially the same species, patterns, and other qualities that define its identity of “maple-beech forest ecosystem.”

The system’s adaptability is a function of general characteristics like diversity, innovation, and feedback, as well as its ability to cope with vulnerabilities specific to its situation and to make deeper transformations if needed.

Importantly, the system is understood to be a “complex adaptive system” that is not static but is constantly adapting to change—change that is often unpredictable.

So when we intervene in a system – for example, a coastal dune ecosystem – to build its resilience, we are trying to guide the process of adaptation so that we can preserve some qualities and to allow others to fade away—all while retaining the system’s essential identity.

And this is a key point:

Building resilience is not about “bouncing back” to some previous state of being. Especially when that previous state of being wasn’t great for everybody.

Building resilience is about maintaining the true “identity” of a system or community, despite ever-changing circumstances.

It’s a state of being, not an end state.

And so when we build off the empirical evidence gathered from the field of resilience science, while recognizing the range of systemic challenges our communities face, we can come up with a definition of community resilience that looks a little like this:

Community Resilience is the ability of a community to maintain and evolve its identity in the face of both short-term and long-term changes while cultivating environmental, social, and economic sustainability.

But why work at the community level at all, when so many of the issues we face are national and global in scale?

There are a number of reasons, but I want to touch upon three very briefly.

First, working at the local level makes practical and political sense, at least in the U.S., where a lot of public policy and infrastructure investment is determined at the local, regional, and state level.

It also makes sense because – as we’ve seen with climate and a whole host of other large-scale issues – ambitious federal policy is almost completely handcuffed by partisan gridlock.

Second, a number of our vulnerabilities are a result of our dependence on globalized food, energy, and financial supply chains that are extremely brittle and susceptible to shocks. So re-localizing where much of our food, energy, and goods come from builds our resilience.

And re-localization – especially when it’s about services that are owned by and for members of the community – can reduce the source of crises like climate change while providing for tangible economic benefits to the community.

Third – and I know it sounds like a cliché – but our greatest resource is ourselves.

A study conducted in New York after Hurricane Sandy showed that the strength of social relationships and networks was one of the single biggest determinates of how badly people were affected by the storm and how able they were to recover afterwards.

No matter how interconnected we have become in the digital age, when push comes to shove it’s the relationships with people around us that matter the most.

Which gets me to the Six Foundations…

As I mentioned earlier, Post Carbon Institute recently published a report that draws on some of the most compelling recent thinking about resilience from academia, sustainability advocacy, and grassroots activism, as well as PCI’s own prior work.

At the risk of over-simplifying things, we arrived at six key elements… characteristics… tenets… that we concluded are foundational to successful community resilience building efforts.

They don’t need to all be present in every community effort or project, but in our view they are necessary components of an overall community resilience building.

Number one: people.

Too often, community resilience building is focused on large-scale infrastructure and led by policymakers and planners. But communities are products of human relationships and resilience building is most effective when local stakeholders are engaged and invested. They are often the most knowledgeable about the community’s opportunities and challenges, and best-suited to act on them through existing economic, political, and social relationships.

Ultimately, it’s only the people of a community who can define its identity. And that identity is not just the qualities of the community it wishes to keep, but also those it wishes to change, along with its vision for the future.

Of course, in practice, envisioning a shared community identity will be messy, multi-faceted, and constantly open to question. But opening potentially challenging discussions is essential for uncovering not only inequities and vulnerabilities, but also opportunities and resources.

Two, systems thinking.

As touched upon earlier, the issues our communities face are of a global nature, highly complex, and intertwined. And communities are themselves made up of complex physical, cultural, political, and environmental systems. These are all complex, adaptive systems and so we can’t approach them as if they were linear problems.

This means uncovering and understanding some of the threads that tie various systems to one another, and what pulling on one area of the tapestry might mean for the rest of it.

For example, when RE-AMP, a coalition of groups in eight Midwest states, set themselves to cutting carbon emissions, they targeted the electricity system – shutting down coal plants and replacing them with renewable energy. But they quickly realized that going after dirty coal plants before building clean energy capacity would backfire… If renewables weren’t ready to take the load then new coal plants would be built instead, locking the region into coal infrastructure for decades to come.

Three, adaptability. When complex systems are resilient in the face of disruption it is because they have the capacity to adapt to changing circumstances, thanks to system characteristics like diversity, modularity, and openness.

For communities, what matters is that resilience is understood as a quality to continually cultivate by taking on the right patterns, not a goal to be achieved by ticking off a list of characteristics.

Andrew Zolli, author of Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back outlines four things that are happening all the time in a resilient community:

- Building regenerative capacity.

- Sensing emerging risks.

- Responding to disruption.

- Learning and transforming.

Initiatives, activists, and politicians come and go, but if resilience building is ingrained in the community culture, it can evolve as the community evolves.

Four, transformability. Community resilience-building efforts can be transformational by tackling those aspects of the community that need fundamental change, and sowing the seeds of transformation generally for when change is needed in the future.

Communities generally adapt as the world around them changes. But if adaptation happens too slowly or is constrained, challenges can outpace the ability to cope and eventually threaten overall resilience.

Transformational efforts are purposefully disruptive to the system, changing some of its functions and structures so that it can build resilience in ways more suited to the new reality.

But transformation is also key to addressing elements of the community that need to change not because of new circumstances but because they were wrong to begin with: racism, inequality, corruption, lack of opportunity, etc.

Five, sustainability. Sustainability starts with the obvious but still often ignored observation that our actions are ultimately limited by the carrying capacity of our finite planet, and that we are already running afoul of this limit.

It presents us with a non-negotiable yardstick against which all our actions, goals, and plans—even those that build community resilience — must be measured.

Without taking sustainability into account, community resilience building efforts could wind up as costly failures or even reduce the community’s longer-term resilience. For example, if passenger vehicles can no longer serve as a primary mode of transportation in the decades to come, then perhaps spending billions of dollars to retrofit tunnels for storm surges might not be the wisest strategy in the long-run.

And last but not least, courage. Community resilience building is not an engineering problem that we can solve just by knowledge and skill. It is a social undertaking, involving thousands or even millions of people and their most meaningful relationships, hopes, and fears. It confronts us with the worrying threats of global crises and compels us to engage with people with whom we may disagree—perhaps quite strongly.

We need motivation and emotional strength to take on such personally challenging work. Individuals need courage to speak out about their views and needs, and make themselves personally vulnerable. Communities, too, need courage to create space for difficult conversations, make far-reaching investments and policy changes, and risk sharing political and economic power.

We need courage to face these challenges head on, to collaborate and speak up, and to stick with the work — work that won’t be easy and likely will never be completed.

I want to end with a plea: If you come away from my babbling with only a few takeaways, I’d like them to be these three:

- Community resilience is an ongoing process, not a destination: A state of being, not an end state.

- Resilience is not about “bouncing back” to the way things used to be. For one thing – as we discussed when talking about the E4 crises – those days are over. For another, those days weren’t great for everyone. This I know you all. And

- Building community resilience is not something we do for other people or even other species. It’s something we do with them.

I think there is a clear need and opportunity for community-based organizations like Community Action Agencies to take a leadership role in building community resilience. I hope you feel the same way.

Thank you.

Community is where Yin (the nitty gritty details of real life in our every day; including with our housemates, neighbours and other community members) meets Yang : the world of our ideas, ideals, “philosophies”, ideologies and perhaps most importantly, self-image, meet. Community is where learning and growth happens , or doesn’t, if we are unwilling to face the certain conflict as well as the support and reciprocity. Dealing with conflict honestly and with ownership of our part in it is honouring of our relationships.

the “E4 crisis graphic” needs to replace “equity” with “population”. the more people struggling for a depleting resource base, the lower the net-energy and associated inherent equity of life for everyone. this means it is harder it is for equity to exist.

i realize controlling human breeding (or even talking about it) is taboo, but an article on resilience when only mentions population once, is missing the mark.