How Does Pandemic Change the Big Picture?

March 25, 2020

As of 2019, the Big Picture for humanity was approximately as follows. Homo sapiens (that’s us), a big-brained bipedal mammal, had spent the Pleistocene epoch (from 2.5 million years ago until 12,000 years ago) developing its ability to control fire, talk, paint pictures, play bone flutes, and make tools and clothes. Language dramatically enhanced our sociality and helped enable us to invade and inhabit every continent except Antarctica. During the Holocene epoch (the last 12,000 years), we started living in permanent settlements, developed agriculture, and built state societies with kings, slavery, economic inequality, full-time division of labor, money, religions, and armies. The Anthropocene epoch (more of a brief interlude, really) dawned only a couple of centuries ago as we humans started using fossil fuels, which empowered us dramatically to grow our population and per capita consumption rates, mechanize production and transport, and basically dominate the entire planet. The mechanization of agriculture, by making the landed peasantry redundant, led to mass urbanization and quickly pumped up the size of the middle class. However, the use of fossil fuels destabilized the global climate, while also vastly increasing existing problems like pollution, resource depletion, and the destruction of habitat for most wild creatures. In addition, over the past few decades we learned how to use debt to transfer consumption from the future to the present, based on the risky assumption that the economy will continue to grow forever, thereby enabling future generations to pay for the lifestyle we enjoy now.

As of 2019, the Big Picture for humanity was approximately as follows. Homo sapiens (that’s us), a big-brained bipedal mammal, had spent the Pleistocene epoch (from 2.5 million years ago until 12,000 years ago) developing its ability to control fire, talk, paint pictures, play bone flutes, and make tools and clothes. Language dramatically enhanced our sociality and helped enable us to invade and inhabit every continent except Antarctica. During the Holocene epoch (the last 12,000 years), we started living in permanent settlements, developed agriculture, and built state societies with kings, slavery, economic inequality, full-time division of labor, money, religions, and armies. The Anthropocene epoch (more of a brief interlude, really) dawned only a couple of centuries ago as we humans started using fossil fuels, which empowered us dramatically to grow our population and per capita consumption rates, mechanize production and transport, and basically dominate the entire planet. The mechanization of agriculture, by making the landed peasantry redundant, led to mass urbanization and quickly pumped up the size of the middle class. However, the use of fossil fuels destabilized the global climate, while also vastly increasing existing problems like pollution, resource depletion, and the destruction of habitat for most wild creatures. In addition, over the past few decades we learned how to use debt to transfer consumption from the future to the present, based on the risky assumption that the economy will continue to grow forever, thereby enabling future generations to pay for the lifestyle we enjoy now.

In short, the Big Picture was one of ever-increasing power and peril. Suddenly it has changed. A pattern of furious economic growth, consistent over many decades since the dawn of the Anthropocene (with only occasional interruptions, primarily consisting of the Great Depression and two World Wars), has slammed precipitously into the wall of pandemic (un)preparedness. In an effort to limit mortality from the novel coronavirus, governments around the world have put their economies into a state of suspended animation, telling most workers to stay home and to avoid direct contact with others.

How is this development impacting trends that were already underway? Will future generations look back on the coronavirus pandemic as a blip or a game changer? Let’s review a few of the major trends that developed during the Anthropocene and engage in a little informed speculation about how they might be affected by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Climate change: In China, lockdowns of workers and closures of companies have led to a dramatic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Over the coming weeks, emissions for the world as a whole could fall by ten percent or more. Note to climate warriors: don’t cheer too loudly; folks who are out of work won’t appreciate gloating greenies.

The world’s response to the coronavirus undermines the argument that governments cannot reduce carbon emissions because doing so would hurt their economies. Clearly, national leaders felt that the more immediate (though, in the larger scheme of things, much less significant) threat of pandemic justified shutting down commerce. Climate activists should now feel emboldened to make the following case: If economic degrowth is what it takes to preserve a habitable biosphere, then world leaders can and must find fair and humane ways to reduce society’s scale of energy usage, resource extraction, manufacturing, and waste dumping—all of which contribute to climate change.

However, the pandemic is not good news for the transition to renewable energy. Supply chains for solar and wind companies have been disrupted, and demand for new installations is down. And with super-cheap oil and gas in the offing (see “Resource Depletion,” below), market forces are likely to hinder rather than help both the renewables industry and the shift to electric cars.

Economic inequality: For the gig economy, and for people living paycheck to paycheck (which includes up to 74 percent of Americans earning hourly wages), the coronavirus lockdown is a catastrophe. Over the short term, existing economic inequalities will result in highly unequal levels of sacrifice and suffering. It may be relatively easy for low-wage workers to rationalize a mandated week or two at home as a forced vacation, but if tens of millions of Americans with no savings experience several months without income, regional social stresses could build to the breaking point. That’s one reason government officials are talking about cash handouts.

Link to original article with chart

Over the longer term, recent absurd levels of inequality could get seriously snipped. In his book The Great Leveler, historian Walter Scheidel argues that, in the past, economic inequality has been reversed most dramatically by what he calls the “Four Horsemen”—mass mobilization for warfare, transformative revolution, state collapse, and plague. Currently many governments are undertaking economic re-allocation efforts equivalent in scale to those seen in the World Wars. For example, Denmark is paying 75 percent of wages (for salaries up to ~$50k/year) for companies that would otherwise have to lay off workers, for a period of three months. This not only enables quarantined workers to survive, but allows them to stay on the payroll and not have to go through a rehiring process later.

Thus, the current pandemic might arguably qualify as two of Scheidel’s Horsemen (mass mobilization and plague). The investor class is witnessing capital destruction at a prodigious rate and scale, while government efforts at maintaining civility and social well-being may entail providing a safety net for those with the least. Of course, this isn’t the way social justice advocates envisioned reining in inequality, but the result may end up being equivalent to another New Deal, and possibly even a Green New Deal.

Biodiversity loss: The novel coronavirus pandemic almost certainly began in wild animal markets in Wuhan, China. As Carl Safina put it in a recent article, “Humans caused the pandemic by putting the world’s animals into a cruel blender and drinking that smoothie.” While there have been other zoonotic epidemics in recent years, including HIV, the Marburg virus, SARS, and the 2009 H1N1 “swine flu” pandemic, the global coronavirus outbreak could provide a teachable moment, when wildlife conservation organizations can call successfully for an international moratorium on the trade or sale of any non-domesticated animal species (with zoos providing a highly regulated exception).

Otherwise, don’t expect much of a change in the overall declining trend in the numbers of insects, reptiles, amphibians, and wild birds and mammals with which we share this little planet.

Overpopulation: A few cynical millennials have called the novel coronavirus the “Boomer Remover” due to its tendency to attack the elderly with greatest virulence. Because humanity has recently been adding 80 million new members per year (births minus deaths), an erasure of one year’s net growth in population is possible in a worst-case scenario. However, the potential for a short-term moderation of our overall pattern of demographic expansion could be at least partly offset by the results, starting nine months from now, of hundreds of millions of people of reproductive age worldwide staying home for weeks with little to keep them busy. For wealthy nations with falling fertility levels, a much bigger threat to human population stability will likely continue to be posed by the buildup of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the environment. For poor nations with high population growth trends, equal education opportunities for everyone regardless of gender will substantially help reduce growth rates.

Resource depletion: With manufacturing on the skids, demand and hence prices for most commodities are plummeting. The world’s most economically crucial commodity, oil, has seen its price fall from $50 a barrel to close to $20 (as of this writing); some analysts are forecasting prices in the single digits. With oil usage crashing, petroleum storage capacity will run out, at which point producers will have no choice but to mothball some oil wells. Oil companies will likely be bailed out, but cannot be profitable under current conditions. The prospect of ever ramping world oil extraction rates back up to recent levels seems dim. It is likely, then, that the long-anticipated moment of the world oil production peak has already occurred, with little fanfare, in November, 2018.

Of course, the blowout in oil markets is a result of economic disaster rather than sound policies of resource conservation. Therefore, adaptation on the part of industry and society as a whole will be chaotic. The international implications are fraught and hard to predict: several key Middle Eastern nations will see their economies shredded by low oil prices, and Great Powers (specifically, China and Russia) may seek to take advantage of the moment by seeking to realign alliances in the region.

Pollution: Marshall Burke of Stanford University has recently written that “the reductions in air pollution in China caused by this economic disruption likely saved 20 times more lives in China than have currently been lost due to infection with the virus in that country.” Reduced rates of manufacturing and consumption should help to reduce overall pollution, but of course this is the side effect of crisis, not the result of sound policy. Therefore, without environmental policy interventions, there’s no reason to expect pollution reduction benefits to be sustained. Just one example of how some temporary benefits could be balanced by new harms: The use of single-use plastics is likely to increase during the pandemic response.

Global debt bomb: The world economy is again in a deflationary moment, as it was in 1932 and 2008. For central banks and governments, all fiscal efforts will be geared toward re-inflating an economy that is otherwise hissing and flattening. There is a heightened risk that investors will realize that, in a no-growth world, their financial instruments are inherently worthless, forcing not just a collapse of the market value of stocks, but a repudiation of the very rules of the game. However, since the coronavirus epidemic itself will eventually subside, the more likely outcome is a period of defaults and bankruptcies mitigated by heroic levels of Fed bond purchases, and government bailouts (of the oil and airline industries, just for starters) and deficit spending. Eventually, if money printing goes exponential, hyperinflation is a possibility, but not soon. Big takeaway: the financial system has been destabilized and, like the oil industry, may never return to “normal.”

* * *

Let’s return to the question posed above: Will humanity look back on the coronavirus pandemic as a blip or a game changer? The likely answer depends partly on how long the pandemic lasts, and that, in turn, will depend largely on how soon tests become widely available, and when treatments and vaccines are found. US Government documents marked “not for public release” suggest significant shortages not just of medical equipment, but also of general goods over the next 18 months for government, industry, and private citizens, if solutions are not quickly forthcoming.

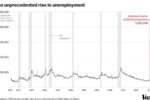

The level at which the game is changed also depends on the degree of downturn in employment and GDP. Fred Bullard, President of the St. Louis Fed, has gone on record saying that the US unemployment rate may hit 30 percent in the second quarter because of shutdowns to fight the coronavirus, and that GDP could drop 50 percent. This would be economic carnage far beyond the scale of the Great Depression (the United States unemployment rate in 1933 was 25 percent; its GDP fell an estimated 15 percent). If the global economy falls that far, and remains locked down even for a few weeks, label the coronavirus “game changer, big time.”

But a change to what? Dystopian possibilities come only too readily to mind. However, in conversation, some of my think-tank colleagues have suggested the pandemic could turn out to be a “Goldilocks” crisis that would disrupt the global order just enough, and in such a way, as to foster a response that sets at least some societies on a trajectory toward cooperation, redistribution, and degrowth.

First, governments often deal with shortages (foreseen in the report cited above) through the tried-and-true strategy of quota rationing. As Stan Cox details in his indispensable book Any Way You Slice It: The Past, Present, and Future of Rationing, quota rationing doesn’t always work well; but when it does, the results can be fairly admirable. During both World Wars, Americans participated enthusiastically in rationing programs for food, tires, clothing, and more. Britain continued its rationing programs well after the end of WWII, and surveys showed that, during the period of rationing, Britons were generally better fed and healthier than either before or after. In most imaginary scenarios for deliberate economic degrowth, quota rationing programs for energy and materials figure prominently.

Cox concludes that rationing programs tend to be more successful when people are united against a common enemy, and when shortages are believed to be temporary. Despite President Trump’s efforts to dub it the “Chinese virus,” SARS-Cov-2 has no inherent nationality, nor is it Democrat or Republican. It is indeed a common enemy, and people tend to become more cooperative when faced with a collective threat. Further, epidemiologists agree that the threat will have an end point, even if we don’t know exactly when that will be. Therefore, conditions for success in rationing exist, and rationing could help foster more communitarian and cooperative attitudes overall.

Also, as discussed above, the pandemic has the potential for significant economic leveling. Historically, not all leveling moments featured increased cooperation: when initiated by state collapse or transformative revolution, leveling has been accompanied by widespread suffering and bloody conflict. However, during the great leveling moments of the twentieth century—the Depression and the two World Wars—Americans managed to pull together with a sense of shared sacrifice.

Over the longer term, we are still faced with the challenges of climate change, resource depletion, overpopulation, pollution, and biodiversity loss. While the pandemic might have minor or temporary spinoff effects that ameliorate these problems, it won’t solve them. Significant, sustained collective effort will still be required to transform energy systems, economies, and lifestyles (though the pandemic could transform economies and lifestyles in unpredictable ways). If the coronavirus response puts us on a cooperative footing, all the better. Of course, that would be at the expense of currently unknown ultimate numbers of fatalities and sicknesses, as well as widespread fear and privation. The potential bits of silver I’ve mentioned are the linings of a cloud; but, as Monty Python can still remind us via YouTube, it’s always good to look on the bright side of life.

Image via Pixabay