Greece Diary

July 10, 2015

I was in Greece from June 23 through July 5, and, while I had no meetings with government officials that might give me insider information on how events there are likely to unfold, nevertheless the experience was both enlightening and disturbing, and is worth relating.

Travel to Greece came at the invitation of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, which had organized a conference on philanthropy and sustainability (here’s the text of my talk). The Foundation constitutes the largest philanthropic organization in the country and from what I can tell it is doing remarkable work in helping the people of Greece deal with their ongoing economic crisis. Stavros Niarchos has spent $100 million so far on jobs-creating projects in technology innovation and cultural preservation, and has promised another $200 million for the years to come.

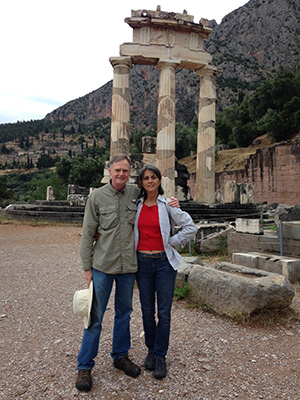

Since Stavros Niarchos generously offered to pay for a plane ticket for my wife Janet too, we decided to celebrate our 20th wedding anniversary by seeing some sights—which in Greece inevitably includes ruins—and spending some much-needed tourist dollars.

Over its long history, Greece has certainly seen spectacular ups and downs, with its better moments providing the cultural underpinnings of western civilization. Sitting and strolling among the fallen pillars of the Acropolis and the Agora—where Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle hung out with their respective flocks of disciples, drinking the ancient equivalent of espresso while discussing truth, beauty, and good governance—couldn’t help but put me in a philosophical mood. These ancient people built in stone and inscribed their ideas on tablets. Yet how fragile their achievements proved to be in the face of economic decline and the onslaughts of invaders. In comparison, our vastly greater modern material achievements (thanks to the power of fossil fuels) have been expressed in buildings with an average 50-year life expectancy, and with writings preserved on media that reliably self-destruct in practically no time at all. What will we leave behind?

But I didn’t travel 6800 miles just to bemoan the fate of industrial society in general terms; I can do that perfectly well from the comfort of my home office. I wanted to see first-hand what’s going on with the Greek economic crisis. Janet and I arrived in the country just as the banks closed, and left the day of the national referendum. The situation there is complicated (for an excellent overview, read Brian Davey’s essay) and evolving so quickly that what I’m writing now might seem dated as soon as it’s published. Nevertheless, readers may find a few first-hand impressions helpful.

For tourists, Greece holds few hardships. Throughout our visit, ATMs were still dispensing wads of 50-euro notes—which we needed as restaurants and hotels gradually stopped accepting credit card payments. But for Greeks themselves, these are increasingly hard times. They face not just the practical inconvenience of being limited to withdrawing a maximum of 60 euros per day from their accounts (if they can find an ATM that still has cash), but also the business nightmare of maintaining credits and payments with banks shuttered, as well as the psychological burden of knowing that things are likely to get much worse, and soon. Greece’s economy has shrunk by 25 percent in recent years as a result of the global economic slowdown and the austerity measures insisted upon by its creditors; I would guess that it has contracted by at least another ten or fifteen percent in just the past two weeks.

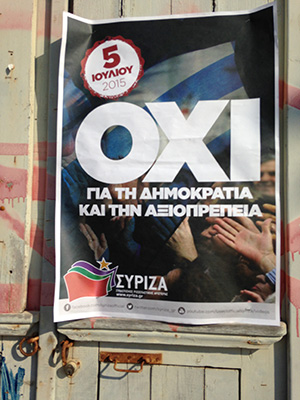

Naturally, I was interested in gleaning opinions from cab drivers, hoteliers, and waiters wherever we stopped. Business owners tended to favor a “yes” vote in the referendum (basically a vote of no confidence in the bargaining position of the socialist Syriza governing party, and a plea to remain within the eurozone regardless of the cost). But most ordinary Greeks we spoke to in Athens planned to vote “no” (“oxi” in Greek) as a show of support for Syriza and a thumb of the nose to the Germans, who are insisting on further austerity. As it turned out on Sunday, the “no” votes predominated, with more than a 60 percent majority.

That has infuriated the Germans and the central bankers, but the vote actually resolves nothing. The ancient Greeks spun the myth of Scylla and Charybdis, illustrating a requirement to choose between two unacceptable options; modern Greeks are living that myth. If they accept further austerity, it will just mean more unemployment and another crisis in a few months. If the debt is “restructured” by giving the Greeks longer to pay, a little more time can be purchased—but another crisis remains inevitable. Even if Syriza prevails in negotiations and much of the nation’s debt is cancelled (everyone knows the Greeks can’t pay it), that guarantees no happy ending. The nation’s pension system is too generous to be sustainable and Greece will simply run up more deficits—and the government needs an infusion of cash now if catastrophe is to be averted; that means more debt. Exiting the euro and bringing back the drachma would entail the loss of a substantial portion of the value of savings. Wealthy Greeks, who already keep most of their money in offshore accounts, might leave altogether.

Any way you look at it, the people of Greece are headed toward misery. And you can see it on their faces. Early in our trip, we would occasionally be approached by old women in peasant garb (possibly immigrants) seeking to sell us little pocket-sized packages of tissue for a euro apiece. By the end of our journey, some of the tissue-sellers were young and well dressed. We spent a couple of days on the gorgeous island of Hydra, where there are no cars (luggage is transported by donkey). Even there the good-natured Greeks we encountered were long-faced. We tried to express our commonality by saying, “However it goes, we wish you the best; after all, it could be our country next.”

In the end, this is an end-of-growth dilemma. If Greece’s economy were still expanding at its 1990s rate, there is at least a chance that the government could repay its debt. But that kind of growth is now unachievable. And as the whole global economy sputters, it is nations like Greece, which live largely from tourism and import all their oil, that will likely confront growth limits first.

Lurking in the background is the immigration question. Refugees from political chaos in the Middle East, and from worsening African poverty, have fed rapid population growth in Athens (and Istanbul as well). Immigration has boosted GDP in some ways (wealthy Syrians relocating to Istanbul have driven up property values), but it has also led to the requirement for more investment in schools, roads, and other infrastructure, and hence more borrowing to finance such projects. This is a problem for Europe as a whole, but it’s the entry points (Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Spain) that bear the brunt. No doubt European nations situated further north would like a firewall against this tide of immigrants, which can only expand as the century wears on. One articulate Italian gentleman living in Greece, whom we spoke with at length over a delicious dinner at an Athenian taverna, speculated that an unspoken subtext of the debt crisis might be that Germany is willing to see Greece—and maybe eventually another country or two—exit the euro, and perhaps the European Union as well, so as to create a failed-state buffer region to either absorb or discourage the immigrant influx.

What should the Greeks do? That’s hard to say, and it’s up to them in any case. If, as it now seems, the design of the eurozone was fatally flawed from the outset, then Greece might as well make its exit now. There’s speculation that Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras may be playing his hand in such a way as to force Germany to push Greece out of the euro; this would play well to his domestic constituency, which has come to see the Germans as villains of the scenario. Meanwhile many people in Germany continue to view the Greeks as lazy and Tsipras as incompetent—characterizations that are more than a little simplistic. My guess is that a Grexit will indeed occur soon, and that will mean many more weeks of chaos and uncertainty for the Greeks and for the rest of Europe as well.

Greece offers an opportunity to study the challenges and opportunities of the end of economic growth for those in the “developed” world. But it’s more than a historic test case; Greece is a nation of 11 million people who face real hardship. Wish them well; you might be next.

—

For more on what’s happening in Greece see e.g., In Athens’ street markets, a Greek tragedy plays out (The Guardian).

So much media coverage for a tiny country of only 11 million people. That is smaller than the population of Cairo, The eleventh largest city in the world. It is only half the population of Shanghai.

It is said Germans directly involved in the global economy love to have Greece in the EU because it keeps the value of the Euro lower than it would be if Germany stood alone. Thus, this improves their exports.

Too much debt in the world and not enough net energy for that debt to ever be paid off. Huge debt write-offs are coming. There is no other possibility. Welcome to debt holidays.

Globally, interest rates have declined, enabling fossil fuel companies to take on huge debt to “drill-baby-drill.” Low interest rates benefit those closest to the primary lender. Those who are in on the take want zero interest or negative interest rates. Those on the periphery enjoy low-cost loans, but wonder why their money doesn’t go as far, and why they don’t earn interest on their savings. We have created a machine for sucking the life out of an economy and we don’t understand how to turn it off. Any rise in interest rates makes the whole machine sputter and shake.

Would that make it more difficult to extract wealth from the Greek economy and offshore it? If so, it might be a good thing.