Export Stupidity

March 27, 2014

Congress is holding hearings this week on the possible lifting of a US oil export ban instituted in the 1970s to promote national energy self-sufficiency and has invited a number of “experts” with dubious ties to the oil and gas industry to explain to them why it’s such a good idea. Following Russia’s near-annexation of Crimea, American politicians are intent on undercutting Russian president Vladimir Putin’s greatest geopolitical asset—his country’s oil and natural gas exports. If the US could supply Europe with large amounts of fuel, that would reduce the Continent’s dependency on Russia while depriving Putin of needed revenues.

Lawmakers from both parties are also using the hearings to urge the Obama administration to speed up natural gas exports as a hedge against the threat of a conceivable Russian cutoff of gas supplies to Ukraine and other countries. Four Central European nations—Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and the Czech Republic—have already made formal requests for US exports.

There’s just one tiny problem with all these fervent desires and good intentions. On a net basis, the US has no oil or gas to export.

Sure, our nation produces a lot of these fuels, and the amounts have been growing in recent years. But the United States remains a net importer of both oil and natural gas. Let me repeat and emphasize that: the United States remains a net importer of both oil and natural gas.

In 2013, the US produced about 7.5 million barrels of crude oil per day, but imported just about as much. While the nation’s rate of domestic production is currently surging, it will likely top out at about 1.5 mb/d above current rates and then start to decline. The likely speed of the decline is a matter of some controversy: the Energy Information Administration forecasts a long plateau and slow taper, while our in-house analysis at Post Carbon Institute indicates a sharper drop-off. Either way, it is extremely unlikely that America will ever again be a net exporter of oil.

Last year the United States produced 24.28 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, an all-time record amount. However, we still imported 2.5 tcf of gas (11 percent of total consumption). The trend in US gas production rates has leveled off and (according to our in-house analysis) is likely to begin declining in just the next few years, just about the time new liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals will be ready for business.

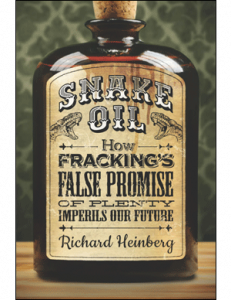

To be sure, extraordinary claims have been made for America’s oil and gas potential, now that the industry has unleashed fracking and horizontal drilling technologies on shale formations in Texas, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere. But, as I argued in my book Snake Oil: How Fracking’s False Promise of Plenty Imperils Our Future, those claims are wildly overblown. A far more accurate assessment of the industry’s prospects comes from its own premiere publication, Oil & Gas Journal, which reports asset write-downs approaching $35 billion among 15 of the main shale operators. The Journal cites “. . . recent analysis by Energy Aspects, a commodity research consultancy, showing 6 years of progressively worsening financial performance by 35 independent companies focused on shale gas and tight oil plays in the US.” This worsening financial performance comes despite production growth and a general shift of drilling activity away from dry gas and toward higher-profit liquids (crude and NGLs) since 2010.

Oil & Gas Journal cites analysis by Ivan Sandrea, an OIES research associate and senior partner of Ernst & Young London, suggesting that, “Unless financial performances improve, capital markets won’t support the continuous drilling needed to sustain production from unconventional resource plays.” Sandrea forecasts that “Parts of the industry will have to restructure and focus more rapidly on the most commercially sustainable areas of the plays, perhaps about 40% of the current acreage and resource estimates. . . .”

So, just what are we supposed to export?

In fact, talk of oil and gas exports is being driven not by excess production capacity or geopolitical acumen, but rather by old-fashioned profit seeking. The US oil industry currently is frustrated by a mismatch between the petroleum grades increasingly being produced domestically (light crude from the Bakken and Eagle Ford plays) and the grades our refineries are tweaked to accept (heavier grades of crude, for example those from Canada’s tar sands). A lifting of legal constraints on exporting US oil would help refiners and producers sort out this temporary mismatch.

Meanwhile the American natural gas industry is suffering under low domestic gas prices, a problem for which the industry has only itself to blame. During the last few years, shale gas companies over-produced in order to upgrade the value of their assets (millions of acres of drilling leases), thereby driving prices down below actual costs of production. If some US natural gas could be exported via LNG terminals now under construction, that would tend to raise domestic prices. However, this would also undercut promises of continuing low prices that the industry has repeatedly made—promises that have lured the chemicals industry to rebuild domestic production facilities and that have enticed electric utilities to switch from burning coal to natural gas—but hey, those were just words.

This is what all the oil and gas export fuss is really about. As for the notion of making Vladimir Putin quake in his boots in fear of a tsunami of American crude and natural gas—forget it. Putin is indeed probably quaking right now, from laughter.

Perhaps America should instead consider exporting stupidity. It’s a commodity we seem to have in surplus.